Treatment for AMD: the Autorité fines 3 laboratories for abusive practices

The Autorité de la concurrence has imposed fines worth a total of €444 million on three pharmaceutical companies, Novartis, Roche and Genentech, for abusive practices designed to sustain the sales of Lucentis for AMD treatment to the detriment of Avastin (a competitive medicinal product that is 30 times cheaper).

The Autorité de la concurrence's Decision 20-D-11 of September 9 2020, which sanctioned Novartis Pharma SAS, Novartis Groupe France SA, Novartis AG, Roche SAS, Genentech, Inc. and Roche Holding AG, was annulled by a decision of the Paris Court of Appeal dated February 16 2023, which ruled that no anti-competitive practice had been established against these companies. This decision may be subject to an appeal to the French Court of Cassation.

Background

Age-related macular degeneration (AMD) is the main cause of low vision for people over 50 in industrialized countries. It causes severe impairment of central vision, which is particularly present in the form of dark spots perceived by the patient in the middle of its vision.

The Genentech laboratory has developed a drug, Lucentis, to treat AMD. It also developed another medicine, an anti-cancer drug, Avastin. Doctors realised that Avastin had positive effects for patients with AMD, which led to a development of its use, without marketing authorisation (MA), to treat this disease, while Avastin costed 30 times cheaper than Lucentis.

| Lucentis | Avastin |

|---|---|

| €1161/injection | €30/40 /injection |

Following the development of the off-label use of Avastin in the treatment of AMD, public authorities in many countries have initiated research projects aimed at testing the efficacy and possible side effects associated with the prescription of Avastin for AMD treatment.

It is in this context that the Genentech, Novartis and Roche laboratories have implemented a set of behaviours (abuse of collective dominant position) aimed at preserving the position and the price of Lucentis, by curbing the off-label use of the anticancer drug Avastin.

Abuse of a collective dominant position

An abuse of a collective dominant position is a concept of competition law which apprehends a dominant position, not from the position of a single actor but from the market power of companies having close ties with each other.

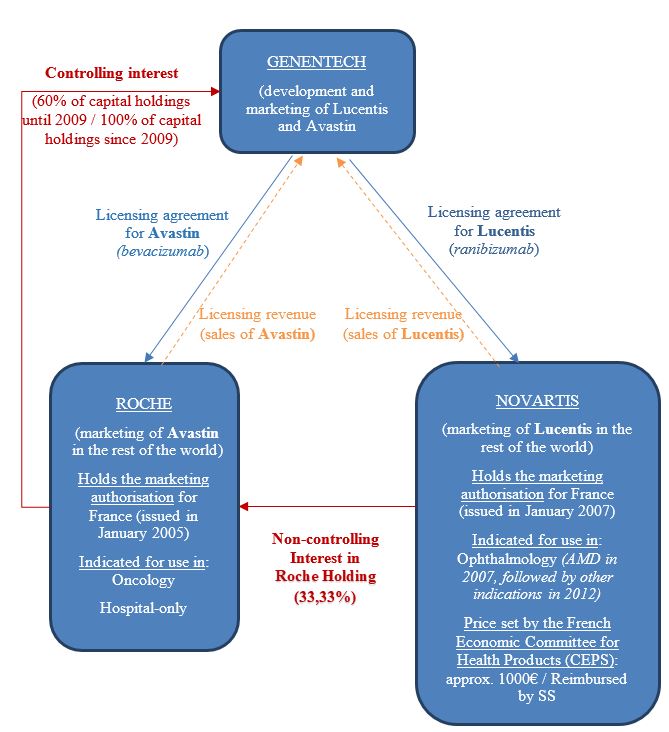

The Autorité considered that the three laboratories - Novartis, Roche and Genentech – have to be examined as forming a “single collective entity” within the meaning of competition law, as regards to cross-holdings and contractual ties between them, including licensing agreements between Genentech and Novartis, on the one hand, for marketing Lucentis, and between Genentech and Roche, on the other hand, for marketing Avastin. Given the differences in the cost of treatment using the two medicinal products, the use of Avastin rather than Lucentis would entail a significant loss of income for each of the three laboratories:

- first, for Novartis, which, as the licensee, earns income from sales of Lucentis on the market in question,

- for Genentech, which, as the licensor, earns licensing revenue on sales of Lucentis on the market in question,

- and for Roche, which, as the major shareholder and, since March 2009, sole shareholder in Genentech, earns dividends on the profits made by this US laboratory.

Novartis disparaged Avastin

Novartis sought ways in which to discredit the decisions taken by some ophthalmologists who, exercising their freedom to prescribe, prescribed Avastin off-label to treat patients in Ophthalmology. It has been fined for disparaging practice, including unjustifiably exaggerating the risks associated with the 'off-label' use of Avastin, designed as a cancer treatment, to treat AMD, and, more generally, its use in Ophthalmology, compared to the safe and well-tolerated use of Lucentis for the same purposes.

This conduct had the effect of reducing the number of off-label prescriptions of Avastin to treat AMD and, more generally, other uses in Ophthalmology. This also had the indirect effect of maintaining Lucentis at supra-competitive price levels and particularly high, and led to fixing the price of Eylea (another competitor medicinal product launched on the market in November 2013) at an artificially high price.

An alarmist and misleading discourse before the public authorities

Novartis, Roche and Genentech have also been sanctioned for colluding in obstructive behaviour and spreading an alarmist and sometimes for having misleading discourse, before the public authorities, regarding the risks related to the use of Avastin to treat of AMD. These practices aimed at obstructing or unduly slowing down initiatives taken by the public authorities to authorise the off-label use of Avastin to treat AMD.

The practices sanctioned are particularly serious as they have been undertaken in the healthcare sector, in which competition is limited and, more specifically, at a time of public debate over the impact on social security finances of the extremely high price of Lucentis - a drug that is fully reimbursed by the French Social Security system - while there has been a significantly cheaper medicinal product, Avastin, that can be used in Ophthalmology.

In total, the Autorité issued a sanction of 444 million euros, which breaks down as follows:

| Laboratory | Fine |

|---|---|

| Novartis | €385 103 250 |

| Roche/Genentech | €59 748 726 |

| Total | €444 851 976 |

Age-related Macular Degeneration (AMD) and its treatment

A matter of public health and finances

AMD, disease of the retina caused by macular degeneration, central part of the retina, is the main cause of visual impairment in patients of 50 years old and more in industrialised countries. Late AMD severely affects central vision, mainly presenting as dark spots in the centre of the patient's field of vision.

AMD has been the subject of a great many scientific studies, in light of the fact that it has major implications for public health and healthcare funding, since the treatments available are particularly expensive.

Treatments

The therapy with medicines belonging to the class of anti-VEGF (vascular endothelial growth factor) was originally developed by US pharmaceutical laboratory Genentech to treat certain types of cancer, by inhibiting the vascular progression of cancerous tumours. Anti-VEGF medications have also been used to treat certain eye diseases involving excessive vascularisation in the eye, as in AMD, by means of intravitreal injections. As a result of its research on VEGF inhibition, Genentech developed two medicinal products: bevacizumab (sold under the brand name Avastin) and ranibizumab, sold under the brand name Lucentis:

- Avastin

Genentech markets Avastin in the United States. In the rest of the world, Genentech granted Roche a licence to develop and market Avastin.

Avastin has been marketed in France by Roche since 2005, under a Community marketing authorisation[1] granted in January 2005, to treat certain types of cancer.

- Lucentis

Genentech markets Lucentis in the United States. In the rest of the world, Genentech granted Novartis a licence to develop and market Lucentis.

Lucentis has been marketed in France by Novartis since 2007 for the treatment of AMD[2], following the issuance of a European Marketing Authorisation issued in 2007. Its indication for use was later extended, in 2011, for the treatment of other eye diseases.

When it was launched, in 2007, Lucentis cost €1,161 per injected dose. The price subsequently dropped several times, between 2008 and 2013, to the current price of €789.50 per dose. In a document on outpatient healthcare expenditure in 2012, the French healthcare insurance fund specified that Lucentis had become the most expensive medicinal product used in outpatient healthcare in terms of reimbursements by the French Social Security system, with a total of nearly €390 million reimbursed to patients, and a high growth rate of around 30% compared to the year before.

The off-label use of Avastin by ophthalmologists

Following the early days of its use in Oncology, some doctors observed that patients diagnosed with both a malignant tumour and AMD also saw an improvement in their AMD when administered Avastin for the cancer.

The use of Avastin to treat AMD (and other eye diseases) then became more widespread in France and worldwide (Europe, United States of America), even after Lucentis had been authorised for reimbursement. Since Avastin is a hospital-only medicine, it was mainly administered in a hospital setting.

When a doctor prescribes Avastin in Ophthalmology, a single vial of Avastin can be used to administer several injected doses, bringing the unit cost per injection to around €30/40, compare to a Lucentis injection cost of €1161. For information, in 2010, a whole vial of Avastin cost €348.10 excluding VAT.

Roche never intended to apply for a marketing authorisation to use Avastin in Ophthalmology, so its use has been off-label, within principle of freedom of prescription framework granted to all doctors.

Initiatives launched by public authorities to ensure the safe use of Avastin

In response to the continuing off-label use of Avastin, the public authorities in many countries decided to launch various research programmes to test the effectiveness and the existence of any adverse effects linked to prescribing Avastin for the treatment of AMD. This research included the CATT study (USA), carried out in 2011 and 2012, and IVAN study (UK), carried out in 2012 and 2013..

In France, discussions on the off-label use of Avastin began in 2006, leading to the launch, in 2008, of the GEFAL trial, funded by the French Ministry for Health and the French National Health Insurance Fund (Caisse Nationale d’Assurance Maladie). The GEFAL trial, the results of which were published in May 2013, concluded that Avastin and Lucentis are equally effective and no differences in the safety profile of each could be identified.

Pending the results of these different trials, the French authorities, including the ANSM[3] in particular, adopted a position of prudence, acknowledging the existence of the usage of Avastin without marketing authorisation for AMD treatment, while urging caution on the part of the ophthalmologists. Nonetheless, in December 2011, the situation changed with the passing of the Bertrand[4] law, which introduced stricter controls on off-label prescription, followed by the adoption in July 2012, by the Directorate-General for Health (DGS), of a directive prohibiting the repackaging of Avastin for ocular injection.

At around the same time, the French legislator initiated studies on tightening control of off-label prescriptions, setting out a new legal framework. This process eventually led to the adoption, in 2014, of a procedure enabling the issue of a Temporary Recommendation for Use (RTU), when the prescribing clinician deems the use of said medicinal product essential for improving or stabilising the patient's clinical status even if there is an alternative appropriate treatment that is approved under a marketing authorisation (French Social Security Finance law No. 2014-892 of 8 August 2014, amended, and the decree on its implementation dated 30 December 2014). This new regulatory framework made it possible to provide a framework for this use, by overcoming the circumstance that a laboratory does not wish to apply for a MA for a drug that is nevertheless used by doctors to treat a condition. This was the case with Roche for Avastin, which has consistently refused to seek Marketing Authorisation for use in ophthalmology. Avastin was the subject of an RTU taken by ANSM for use in the treatment of AMD in June 2015.

Three closely tied actors dominated the AMD market: The collective dominant position of Novartis, Roche and Genentech

The three companies Genentech, Roche and Novartis are tied by significant close structural and strategic links. First, Genentech is connected to Roche and Novartis through licensing agreements for marketing Avastin and Lucentis, respectively, outside the United States. The agreements linking Genentech and Novartis, on the one hand, and Roche, on the other hand, provide for a highly-organised system of feedback, discussion forums and joint management committees.

Second, Genentech, Roche and Novartis have particularly significant cross-holdings:

- Roche was the majority shareholder in Genentech up until 2009 and, since then has become the sole shareholder in the American pharmaceutical company.

- Novartis is one of the major shareholders in Roche, with a 33.33% share of the voting rights in Roche Holding.

[1] All medicinal products industrially manufactured and sold on a domestic market or within the European Union must have been granted a marketing authorisation. Issuing a marketing authorisation permits the marketing of a medicinal product as indicated for one or more treatment(s), following assessment by the medical authorities of the risk/benefits of its use, based on scientific studies.

[2] Community marketing authorisation obtained on 22 January 2007.

[3] Agence nationale de sécurité du médicament - the French national agency for safety of medicines and health products

[4] Law No. 2011-2012 of 29 December 2011, on tightening the requirements regarding the safety of medicinal and health products

Thanks to these structural ties and cross-holdings, Genentech, Roche and Novartis have been able to implement a common strategy in the market. The three companies have strong financial incentives for keeping Avastin and Lucentis separate. Given the differences in the price of the two medicinal products, and the practice entailing making up a number of syringes using a single vial of Avastin, the use of Avastin rather than Lucentis for ocular injection was liable to entail a significant loss of revenue for each of the three companies. And the development of Avastin as an alternative to Lucentis was a "measure" to keep the price of Lucentis very high. Also, the structural ties created by the licensing agreements between them has meant that it was possible for them to be aware of their partners' respective behaviour, and, as a result, ensure that they were all following the same line of action.

Bearing in mind Roche's holdings in Genentech, the commercial and development policies of the two companies are very closely linked, with Genentech depending on Roche to set out its general strategy. In such a situation, Roche had no interest in pursuing a policy that would position Avastin on the market in such a way that it would be detrimental to the interests of its own subsidiary, Genentech.

Together, they form a united entity that enjoyed a dominant position regarding treatment for AMD, which came to an end in 2013 with the arrival of Eylea (Bayer) on the market, which won a 36% share of the market within only 3 months of its market launch in November 2013.

Anticompetitive practices

Objection 1: The disparaging of Avastin by Novartis

(duration: March 2008 to November 2013)

Novartis led a global, well-organized communication campaign that tended to discredit the use of Avastin to treat eye disease, in favour of Lucentis. This campaign targeted ophthalmologists and, in particular, Key Opinion Leaders, doctors recognised in their field who might relay the message put out by the pharmaceutical company. Novartis also spread this message among patient associations and the general public.

The evidence in this case shows unequivocally that the message put out by Novartis was not based on any concern for public health, but was an anticompetitive tactic designed to knowingly stoke fears regarding whether or not it was safe to use Avastin 'off-label' in the field of Ophthalmology, in order to preserve the strong position of Lucentis and its high price.

Novartis was not content to simply discuss the objective differences between Lucentis and Avastin, nor to faithfully present the scientific context relating to the use of Avastin. Instead, it disseminated data comparing Avastin and Lucentis, mainly drawing on a selective and biased presentation of the available scientific data, with a view to playing up the risks related to the off-label use of Avastin to treat AMD and other eye diseases:

- First, Novartis spread a discourse suggesting, and occasionally stating outright, that there was an increased risk of systemic reactions related to the biological properties of Avastin, which are not the same as those of Lucentis, while playing up the supposedly greater safety of using Lucentis.

- Second, Novartis proceeded with a selective and biased presentation of the results of scientific trials comparing the effectiveness and safety profiles of Avastin and Lucentis for use in the field of Ophthalmology. By focusing on certain results out of context, and highlighting the methodological shortcomings of trials while abstaining from presenting their general conclusions, Novartis' presentation of the results available from scientific studies was fragmented and given out of context.

- Third, Novartis was also selective in its presentation of changes made by the European Medicines Agency (EMA) to the Summary of Product Characteristics (SmPC) for Avastin and that for Lucentis. Novartis' discourse regarding these changes suggested that the EMA had decided to make it public that systemic adverse effects had been detected only in the case of Avastin, whereas the EMA had concluded that no distinction could be drawn between the different anti-VEGF therapies, to which Lucentis also belongs. Novartis also only posted any information about the changes to the SmPC for Avastin (which, in any case, is not the product marketed by Novartis), moreover by neglecting to mention that the same changes had also been made to the SmPC for Lucentis.

- Last, Novartis claimed that healthcare professionals who prescribed Avastin 'off-label' risked being held liable under civil and criminal law.

This communication campaign had a real and significant impact on the behaviour of healthcare professionals and, consequently, on the structure of the market. It reduced off-label use of Avastin at many hospitals for the treatment of AMD and, more generally, in Ophthalmology.

Furthermore, by reducing the frequency with which Avastin was prescribed and, thereby, maintaining Novartis in a quasi-monopolistic position, Novartis' discourse had the effect of preventing Avastin from being used in comparative trials organised by the authorities in charge of setting the price of medicinal products and thus to support any reduction in the price of Lucentis.

Thus, these practices had a mechanical effect on the pricing of Eylea, alternative to Lucentis, meaning it was priced at more or less the same list price as Lucentis (10% less).

Objection 2: Practices implemented by the three companies with regard to the public authorities

(duration: Roche: April 2008 to the beginning of November 2013 – Novartis: May 2011 to the beginning of November 2013 – Genentech: April 2011 to the beginning of November 2013)

Novartis and Roche, aided by Genentech, initiated a series of blocking tactics, and their discourse with regard to the French public authorities was alarmist and misleading. These practices were designed to exacerbate their concerns and block any initiatives undertaken by the public authorities to set up procedures for the safe use of Avastin in the treatment of AMD.

As of April 2008, Roche sought to delay the GEFAL trial (Groupe d'Étude Français Avastin versus Lucentis - the French Evaluation Group Avastin Versus Lucentis) by refusing for several months to supply the samples and data required to go ahead with the trial, which had been requested by the ANSM (National Agency for the Safety of Medicines and Health Products) and developing an alarmist discourse regarding the safety profile of Avastin for ocular injection. In all its subsequent communications with the ANSM, Roche continued to mislead the Agency, through a biased presentation of the results of trials that were then beginning to be published.

As of May 2011, Novartis also disseminated a worrying discourse before the public authorities, selecting certain results of comparative studies and presenting them out of context. This discourse was communicated to all the stakeholders in the healthcare sector, stirring up a great many reactions.

As soon as the public authorities made it known that they were considering issuing an RTU for Avastin, Roche and Novartis stepped up their initiatives and contacts with government and health authority representatives. The message at this time included a biased presentation of the process that had resulted in a change to the SmPC for Avastin and highlighted the risks of causing a new health scandal.

Evidence in this case also reveals that, from April 2011, Genentech was systematically involved in the communications between Roche and the health authorities and informed the content of the message to be communicated.

Roche and Novartis acted to delay the GEFAL trial and influenced the health authorities, amplifying their concerns and influencing them to maintain a position of extreme prudence even following publication of the first favourable results of trials comparing Avastin and Lucentis (i.e. updates from AFSSAP, the French Agency for the Medical Safety of Health Products in 2009 and 2011, and a recommendation by the HAS, the French National Authority for Health in 2012).

The discourse also had a direct influence on the decision by the Directorate-General for Health (DGS) to prohibit the off-label use of Avastin, in July 2012, and, more generally, in delaying the adoption of provisions designed to control and ensure safety with regard to the off-label use of Avastin in the field of Ophthalmology.

In so doing, the three companies ensured that Avastin could not be recognised by the French health authorities as an appropriate comparator in trials alongside Lucentis, which would have enabled the authorities in charge of pricing medicinal products to renegotiate the price of Lucentis to bring it down substantially at a much earlier date.

Decision 20-D-11 of 9 September 2020

Contact(s)