The Autorité publishes its study on the competition issues surrounding the energy and environmental impact of artificial intelligence

Background

Following on from Opinion 24-A-05 on generative AI, the Autorité wanted to take its analysis further by examining competition issues surrounding the energy and environmental impact of AI. Today, the Autorité is publishing its first study on the topic and urges all stakeholders to engage with the issues.

The emergence and massive deployment of AI are recent, and the impact of AI is still difficult to measure, in particular given the improvements in energy efficiency and resource management that AI will enable. However, the rapid development of data centres and AI – which is a key priority for France and the European Union – is driving a sharp rise in electricity consumption, considerable pressure on other resources (water, rare metals, land) and a significant carbon footprint.

The Autorité notes that the impact on energy and natural resources raises three types of competition issues:

- difficulties in accessing the power grid and energy prices, which may affect the sector’s competitive dynamics;

- the growing focus on the frugality of AI services (i.e. the search for efficiency that minimises environmental impact), which may foster the development of new offerings enabling certain operators, in particular smaller companies, to compete with the biggest operators in the sector;

- the standardisation underway, in particular the introduction of methods for determining environmental footprint, which appears fundamental to guaranteeing competition between operators based on their respective merits.

In view of the issues identified, the Autorité places particular emphasis on the need for reliable and transparent data on the energy and environmental footprints of AI, in order to ensure effective competition on those aspects. Such transparency, including through the implementation of standards, would also ensure that frugality can play its full role as a competitive parameter. The Autorité stresses, in addition, the need to ensure that access to areas suitable for data centres and to energy, in particular nuclear-generated electricity, is not restricted to certain operators only.

Consequently, the Autorité invites all stakeholders to take note of the issues identified and, where appropriate, to refer any suspected anticompetitive practices, or to seek informal guidance from the General Rapporteur on the compatibility of their projects with sustainability objectives with competition rules.

The energy and environmental impact of artificial intelligence

The energy impact of AI

The rise of AI is accompanied by particularly high energy consumption, due to its substantial electricity requirements, notably to power data centres and high-performance computing infrastructure.

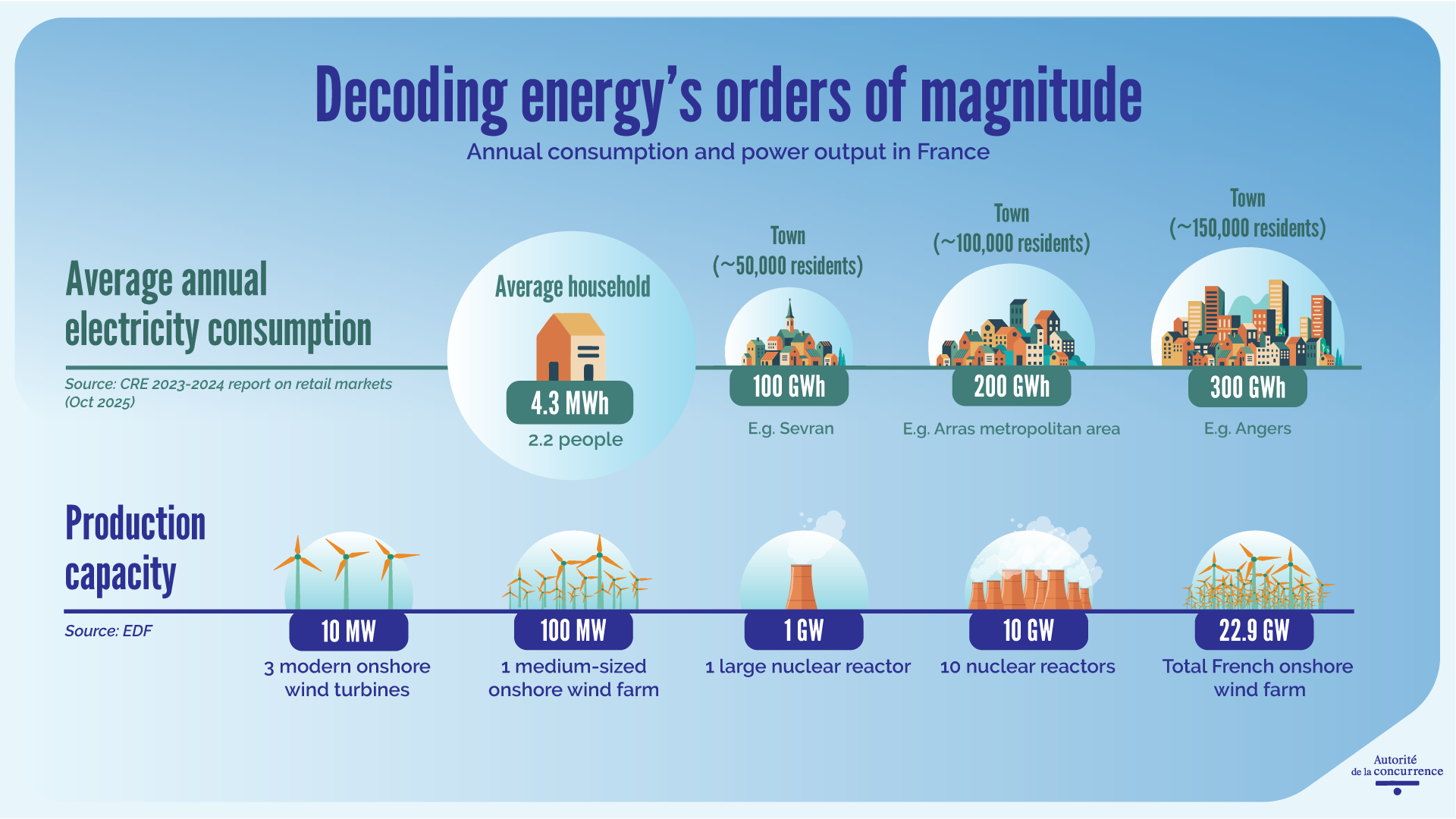

Data centres today account for approximately 1.5% of global electricity consumption, but their local impact is far more significant, and their consumption could, at a minimum, more than double by 2030 as a result of AI, to reach up to 945 terawatt-hours (TWh). In France, data centre consumption, estimated at 10 TWh in the early 2020s, could reach 12 to 20 TWh in 2030 and 19 to 28 TWh in 2035, representing almost 4% of the country’s electricity consumption. As a result, some major operators – in particular US companies – are securing (or have already secured) supply partnerships for decarbonised energy, such as renewable or nuclear energy.

The environmental impact of AI

AI also uses significant resources across the value chain (water, rare metals, land) and has a clear environmental impact. In the absence of available data, however, the study focuses solely on the impact at the data centre level.

By way of example, according to the French Regulatory Authority for Electronic Communications, Postal Affairs and Print Media Distribution (Autorité de régulation des communications électroniques, des postes et de la distribution de la presse – ARCEP), the volume of water – mainly drinking water – withdrawn by French data centres reached 0.6 million m3 in 2023. In addition, the annual growth in the volume of water withdrawn in France remains extremely high, at +17% in 2022 and +19% in 2023. In addition to this direct water consumption, ARCEP estimates indirect withdrawals and consumption, in particular linked to the production of the electricity required for data centre operations, at over 5.2 million m3 per year.

Several studies also suggest that AI has a significant net carbon footprint, despite its potential contribution to energy efficiency and the management of resources such as water. Several digital operators have announced sharp rises in their greenhouse gas emissions (ranging from +30% to +50%), due in particular to the increased energy consumption of data centres.

Competition issues

Based on the above findings and taking into account the competitive environment in the different markets affected by the rise of AI, the Autorité has identified three types of competition issues within the scope of the study.

Access to energy and cost control

Operators face difficulties in connecting to the power grid, as well as uncertainties over energy prices, which may affect the sector’s competitive dynamics.

Public authorities have introduced a number of measures aimed, in particular, at limiting the risk of grid saturation, speeding up the connection of electro-intensive industrial consumers to the power grid, and processing connection requests more efficiently. To a certain extent, AI also tends to reduce the need to concentrate data centres in the same geographic areas. While the inference phase remains sensitive to latency and therefore requires proximity to urban centres with reliable connectivity, the training phase offers greater flexibility in terms of geographic location.

Furthermore, access to energy at a competitive and predictable price is a major issue in a context where electricity is estimated to account for 30% to 50% of a data centre’s operating costs and where, moreover, the energy landscape is characterised by considerable uncertainty. In France, the end of the ARENH mechanism, under which electricity suppliers could purchase nuclear‑generated electricity from the country’s existing power plants at a regulated price between 1 July 2011 and 31 December 2025, has led to the introduction of a dual system:

- the redistribution of EDF’s profits to end-consumers through a universal nuclear payment (VNU). The measure is currently being examined by the French parliament and will soon be subject to an opinion by the Autorité;

- the development by EDF of long-term nuclear production allocation contracts (CAPN). Several orders have already been placed by data centre operators on the basis of the CAPN mechanism, in order to secure their supply of low-carbon electricity.

Other approaches, such as the direct purchase of electricity through power purchase agreements (PPA) from wind or solar energy producers, are also being implemented, in particular by data centre operators.

With regard to access and costs, the Autorité has analysed a number of behaviours likely to raise competition concerns. Beyond the risks of barriers to entry or expansion for smaller operators, the Autorité will pay particular attention to ensuring that the biggest operators in the sector are not able to use their privileged positions to secure energy supplies on advantageous terms. With regard to energy suppliers, as the Autorité and the French Energy Regulatory Commission (Commission de régulation de l’énergie – CRE) recently stated, the CAPN mechanism must not lead to anticompetitive behaviours, such as discrimination, refusal to supply or foreclosure of the market for large industrial consumers, to the detriment of competitors. Lastly, a number of factors suggest that major digital operators could, even if only occasionally, enter energy markets as suppliers, especially abroad.

The Autorité will ensure that competition is based on the merits of each operator and urges companies in the sector to remain vigilant regarding the above issues.

The emergence of the frugality of AI services as a competitive parameter

In response to the energy and environmental impact of AI, the concept of frugality is emerging, defined as the optimised consumption of resources with the aim of minimising environmental impact.

There are a number of signs, on both the demand and supply sides, that frugality is becoming a competitive parameter. For example, on the demand side, both public and private buyers are showing a growing interest in more frugal tools, while, on the supply side, several operators are developing smaller models or providing information about their environmental footprint. A similar phenomenon also appears to be emerging further upstream in the value chain, with a focus on minimising the environmental footprint of data centres in particular.

The Autorité considers that frugality can help to stimulate competition:

- firstly, frugality can affect price: frugality involves cost optimisation based on actual needs, thereby helping to promote the emergence of competitively priced solutions;

- frugal AI can also affect competition from a quality perspective: frugal AI is resource-efficient and has a lighter footprint, and can therefore be adapted to smaller-scale deployments, for example by leveraging existing IT infrastructure;

- lastly, frugality can affect competition in terms of the incentive and ability to innovate: by becoming a key development focus in the sector, frugality can steer part of innovation in this direction, thereby fostering competition through the diversity of innovations.

With regard to frugality and on a non-exhaustive basis, the Autorité has identified several competition risks and urges all operators in the sector to be vigilant. Whether in the case of coordinated behaviour between competitors, or a strategy adopted by a dominant operator, the following may be problematic:

- the adoption of misleading practices regarding frugality, even unintentionally – for example, if the environmental footprint reported is not based on a scientifically robust methodology;

- a failure to disclose information on environmental footprint or frugality, even where there is a demand for such information;

- the limiting of innovation in the area of frugality.

Ongoing standardisation of the environmental footprint

Given the significant environmental impact of AI, it is becoming increasingly important to enhance transparency in this area, in particular to improve comparability. More precisely, this need arises from a combination of three factors:

- companies that model or use AI-based solutions provide little information about their environmental impact;

- there is no shared methodology for operators to communicate on this impact;

- the measures taken to date are difficult to compare, especially given the differences in their scope.

In terms of standardisation, several tools have recently been or are currently being developed. For example, ARCEP and the French Regulatory Authority for Audiovisual and Digital Communication (Autorité de régulation de la communication audiovisuelle et numérique – ARCOM) have co-published a general reference framework for the eco-design of digital services, which presents developments to support the eco-design of AI-based solutions, while a general reference framework for frugal AI has been developed at the initiative of the French Ministry of Ecological Transition, by the French Standardisation Association (Association française de normalisation – AFNOR). Such tools help to support companies but should also be seen as a precursor to standardisation, in particular at the European and international levels.

At the same time, the Autorité has observed the development of a growing number of tools focused on measuring environmental footprint:

- some tools focus on measuring energy and carbon footprints (e.g. Green Algorithms);

- others offer a complete life cycle analysis (e.g. the tool deployed by Carbone 4 for Mistral);

- there are also tools to help design frugal AI solutions (e.g. CodeCarbon or CarbonTracker);

- lastly, several tools offer an impact analysis of deployed solutions (e.g. Ecologits or Ecoindex).

Some operators are advocating for a step further: the introduction of an environmental rating (or score) that would allow for models to be compared based on their environmental impact.

From a competition perspective, all such initiatives can be seen as a move towards standardisation with a sustainability objective, strengthening the role of frugality as a competitive parameter through greater transparency and comparability.

However, several competition issues may arise in the context of this standardisation. On a non-exhaustive basis, the Autorité notes that, whether in the case of coordinated behaviour between competitors, or a strategy adopted by a dominant operator, the following may be problematic:

- the adoption of standardisation tools that are not based on a scientifically robust methodology. To limit the competition risks, the Autorité reminds operators that guaranteeing representativeness in the development of the tool and transparency for its users, as well as requiring the use of third-party verification, are key considerations;

- the adoption of standardisation under conditions that deprive certain operators of its benefits or prevent frugality from serving as a competitive parameter;

- the adoption of practices that impede standardisation, such as strategies aimed at withholding information essential to the development and implementation of the standard or at slowing down or hindering its development process;

- the exchange between competitors of commercially sensitive information, including environmental information, where such exchanges are not objectively necessary for and strictly proportionate to standardisation;

- in the case of multiple, competing standards, the exchange of information between standards developers, such as the alignment of their strategies and products, insofar as such exchanges are not objectively necessary for and strictly limited to the legitimate objective being pursued;

- in their implementation, the adoption of practices that discourage operators from going further than proposed by standardisation.

The study highlights three main competition issues linked to the energy and environmental impact of AI: access to energy, the emergence of frugality as a competitive parameter, and the development of standardisation tools for measuring environmental footprint.

The study aims to contribute to the ongoing debate on those issues by highlighting several key areas of concern, including:

- the need for reliable data on the energy and environmental impact. Such transparency, including through the implementation of standards, would also ensure that frugality can play its full role as a competitive parameter;

- the need to ensure that access to areas suitable for data centres and to energy, in particular attractively priced nuclear-generated electricity, is not de facto reserved for the biggest operators only.

The Autorité invites all stakeholders to take note of the study. Moreover, the Autorité reminds stakeholders that any suspected anticompetitive practices in the sector can be reported to the Autorité, either through a formal referral or via the dedicated reporting platform. Stakeholders can also seek informal guidance from the Autorité on the compatibility of their projects with sustainability objectives with competition rules.

Study

Contact(s)