1 April 2015: Joint purchasing agreements in the food retail sector

The Autorité de la concurrence issues an opinion in which it proposes a grid for the general analysis

of risks arising from the cooperation agreements recently concluded and provides recommendations

The Minister for the Economy, Industry and Digital Affairs and the Economic Affairs Committee of the French Senate have referred to the Autorité for an opinion on the impact on competition of centralised purchasing and listing offices in the food retail sector.

In the context of the investigation, the Autorité has questioned a significant number of economic players (retailers and suppliers) and conducted numerous hearings (20 including 3 professional associations and the French Ombudsman for Agricultural Trade Relations).

CONTEXT

Cooperation agreements

Three partnerships have been formed within an extremely short space of time, shortly before the start of annual negotiations (indeed, after the start as for the last case):

- Système U/ Auchan

On 10 September 2014, Système U Centrale Nationale gave Eurauchan a mandate to negotiate the purchase of part of the national-brand goods sold by its stores. The agreement covers all suppliers of products sold under national brands common to the two retailers (around 300), excluding SMEs and companies providing traditional fresh products, in particular those that come from the agricultural sector (fruit and vegetables, manned cheese, bakery products, patisserie products, meat and fish).

- ITM/Casino

On 7 November 2014, ITM Alimentaire International and EMC Distribution entered into a cooperation agreement aimed at negotiating the purchase of some goods under national brands (excluding retailers’ branded products and traditional fresh products) sold by their respective stores.

This concerns 64 suppliers of consumer goods, chosen once suppliers likely to be in a situation of economic dependency had been excluded. The two distributors set up a joint undertaking (INCAA) that negotiates exclusively with the suppliers covered by the agreement.

- Carrefour/Cora

On 22 December 2014, Carrefour and Provera in turn entered into a partnership agreement, providing Provera with access to Carrefour’s listing offices.

The cooperation agreement is based on an established list of suppliers of national-brand consumer products (103 food and 37 non-food) and expressly excludes products from the agricultural sector, traditional fresh products and private label products.

These cooperation agreements were entered into in the specific context of a price war that was exerting downward pressure on operators’ margins.

Since 2013, the food retail sector has seen a decrease in prices liable to put pressure on operators’ margins. This trend was accentuated in 2014.

The consequence of this decrease in prices may have been that some retailers were obliged to reduce their margins to remain attractive. Indeed the Auchan, Casino, Cora, Intermarché and Système U groups all recorded a global decrease in margins across 2014, while those of the Carrefour group remained relatively stable. These retailers explain that against this backdrop, a cooperation agreement was necessary to improve their purchasing conditions and restore their competitiveness. Failing this, they would eventually find themselves squeezed out of the downstream market as a result of consumer disaffection and/or the loss of stores opting to affiliate themselves to more attractive networks.

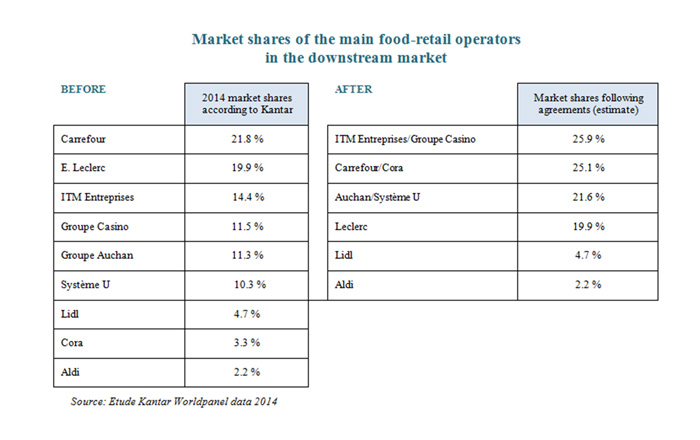

The announcement by Auchan and Système U of their joint purchasing agreements had a domino effect: they were followed by Intermarché and Casino and finally by Carrefour and Provera. The proliferation of these agreements significantly increased the level of concentration and gave significant purchasing power to the operators concerned, who already had significant weight at the retail distribution stage. As a result, following these agreements, the market is mainly distributed between four major purchasers (ITM/groupe Casino, Carrefour/Cora, Auchan/ Système U and E. Leclerc), which together represent more than 90% of the market.

These agreements, which were put into place at the beginning of the annual negotiation cycle, have caused concern among manufacturers and may have destabilised some operators. As a result the public authorities kept a close eye on how commercial negotiations were going. It is in this context that the referral was made to the Autorité for its opinion.

METHODOLOGY AND GENERAL APPROACH

The Autorité firstly stresses that as they stand, none of these agreements fall within the field of merger control. However, this absence of controllability in no way prevents them from being examined from the perspective of anticompetitive practices and in particular regulations governing anticompetitive agreements. Nonetheless, the Autorité also recalls that it is not within its remit, in the context of a referral for an opinion, to qualify the specific behaviour of a particular economic actor. Indeed, only the instigation of litigation proceedings with the due hearing of both parties would allow it to carry out such a qualification.

Commercial negotiations in the food retail sector are characterised by a certain complexity. This is linked notably to the fact the price of sale granted by the supplier reflects a multitude of criteria, as well as to the regulatory provisions that govern them. The agreements that are the focus of this opinion add to this complexity by making a distinction between several categories of suppliers, multiplying the layers of negotiation, and for some of them by making new segmentations between different aspects of the negotiation.

-> In this context, the Autorité’s approach is necessarily nuanced in so far as the agreements in question were concluded in an extremely short space of time. They have also evolved while the investigation has been taking place, in terms of scope, form and number. Finally, analysis thereof depends on numerous parameters, both structural and behavioural, which could vary significantly depending on the categories of products concerned.

COMPETITION RISKS LINKED TO THESE AGREEMENTS

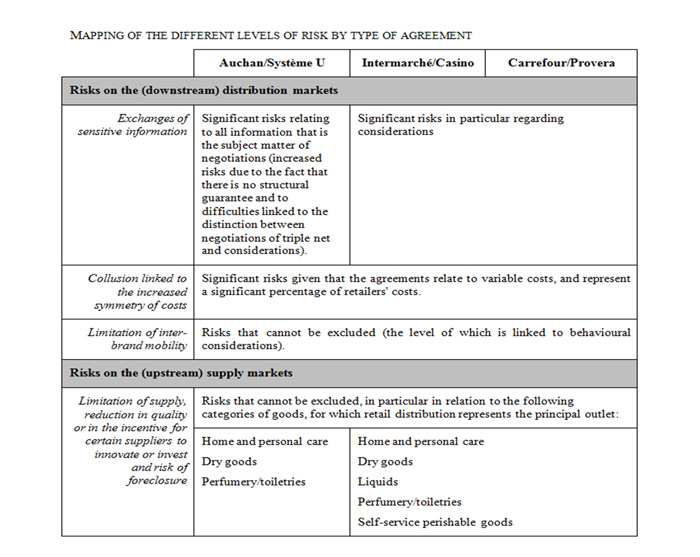

While this type of agreement can have pro-competitive results, in particular in terms of the price levels of consumer goods bought by consumers, the Autorité de la concurrence has nevertheless identified several competition risks on both the upstream and downstream markets.

Risks on downstream markets

- Exchanges of information

Annual negotiations between retailers and suppliers focus on product purchase price, discounts and fees for commercial cooperation. They may be more specific and detail, for example, the product assortment on display, the launch of new products or promotional activities.

Some of this information could be of a sensitive nature if it were to be exchanged between two competing retailers.

In fact such exchanges could allow retailers to compare not only the considerations they are offering suppliers but also the remuneration associated therewith. Such exchanges of information could therefore have the effect of decreasing the considerations granted, whether as regards ranges, the launch of new products or commercial operations. They could also decrease retailers’ incentives to be competitive downstream, in particular by means of their promotional policy, thus having a negative impact on the offer that retailers provide to consumers.

- The symmetry of purchasing conditions

Cooperation agreements can also lead to homogeneity of purchase prices for the principal consumer goods, or even in other cost items such as logistics. Such an increase in cost symmetry can favour collusion on the retail distribution market - all the more so that the costs in question are variable costs and represent a significant portion of retailers’ purchasing.

- Reduction of inter-brand mobility

Cooperation agreements could reduce partners’ incentives to compete for the affiliation of new stores. The cumulative effect of these agreements could freeze a significant proportion of store numbers.

Risks on the upstream markets

- Risks such as limitation of supply, reduction in quality or in the incentive for some suppliers to innovate or invest

A significant number of suppliers questioned stated that the strengthening of the retailers’ purchasing power led to pressure on their margins, such that they deemed it probable that they would have to reduce or limit their investment, as well as the launching of innovations onto the market, or even rationalise their offer.

- Risks of foreclosure of suppliers

Cooperation agreements related to purchasing are liable to cause a decrease in purchase prices for retailers vis-à-vis not only the suppliers involved in these agreements, but also their competitors. In fact, price decreases agreed by the suppliers involved in the agreements can lead to a drop in their competitors’ turnover, due to a volume effect (the sales of less competitive competing suppliers’ will decrease) and/or a price effect (competing suppliers obliged to align themselves with the discounts granted by the suppliers covered by the agreements).

According to their scope and the supplier’s capacity to absorb a decrease in its margins, it cannot, therefore, be excluded that the cooperation agreements in question could aggravate some suppliers’ difficulties, whether or not they are involved in the agreements. The case is the same for any additional considerations that may be demanded by retailers, from which only the biggest suppliers could benefit.

THE SPECIFIC QUESTION OF ECONOMIC DEPENDENCY

The three recently concluded cooperation agreements have led to enhanced purchasing power on the part of all the retailers and, in this respect, are liable to give rise to concerns in relation to the growing imbalance between retailers and suppliers.

Some retailers involved explain that they have chosen, by way of precaution, to limit the scope of their agreements to large-size suppliers, or even to exclude certain suppliers on the basis of a possible risk of economic dependency. However, numerous actors in the sector have expressed fears with regard to the risk that these different partnerships may lead to situations where certain suppliers become economically dependent on retailers, which the latter could abuse.

The investigation has brought to light the existence of practices that call for vigilance

- Delisting practices

In the course of the investigation, numerous cases of delisting or threats to delist were reported. These delistings concerned a variety of goods, including well-known brands and were of varying scope depending on the breadth of the range in question and their duration.

-> In the current context of joint purchasing agreements, such practices - in particular if they were to be generalised - could have a negative impact on competition to the extent that they could lead, in the medium/long term, to a reduction in volumes, a reduction in suppliers’ incentives to invest or even, in extreme cases, to the foreclosure of some suppliers.

- Practices regarding demands for advantages without any consideration in return

Enhancement of retailers’ purchasing power arising in particular from the recent joint purchasing agreements between retailers has also given rise to demands for renegotiation of commercial conditions, which several suppliers believe are unequal. The majority of suppliers questioned stated that they had been faced with demands for considerable deflation of triple net price, which were not accompanied by any proposals of additional considerations by retailers.

Furthermore, ANIA and the Agricultural Affairs Ombudsman highlighted the generalisation of what are known as "margin guarantee" practices, whereby a retailer, without any consideration in return and during execution of the contract, asks its suppliers to offset any loss of margin that this retailer may incur due to a decrease in the consumer retail price of the product in question, in response to a more competitive offer by a competitor.

->Such practices, which have also been closely examined by the DGCCRF under the provision of Title IV on restrictive competitive practices could limit retailers’ incentive to compete, and, particularly if the practice is widespread, could weaken certain suppliers and oblige them to reduce their investments.

Reflections on the effectiveness of the current system for addressing these practices

Several operators have questioned the Autorité as regards the ineffectiveness of the current procedure for addressing abusive practices used by retailers in their relations with their suppliers in a context of enhanced purchasing power of retailers.

The Autorité stresses that these practices, which concern the bilateral relationship between two parties to a contract, essentially fall within the scope of the DGCCRF, in terms of regulations regarding "restrictive competitive practices". It is not until they are likely to compromise the proper functioning or structure of competition that they may be addressed by the Autorité de la concurrence in accordance with Article L.420-2 paragraph 2.

The application of this provision indeed supposes the initial establishment of a state of economic dependency of one undertaking on another, and subsequently, the abuse committed by the latter, in view of its impact on the competitive functioning of the market.

A rapid assessment of decision-making practice and jurisprudence shows that in reality the initial stage is almost never reached, given the cumulative application of very strict conditions. In the past, this approach has led to the rejection of most complaints and it should be recognised that to date the application of this standard has had the effect of neutralising the application of this provision.

In the current context of partnerships between buying offices in the food retail sector, this situation could be a cause for concern in that, without the power to identify a state of economic dependency, the Autorité would not be able to examine the effects of practices that are potentially problematic from a competition viewpoint.

RECOMMENDATIONS

Joint purchasing agreements between operators and their implementation in the context of commercial negotiations carried out with suppliers could potentially be addressed in two ways: on one hand on the basis of the prohibition of cartels, and on the other, on the basis of the prohibition of abuse of a situation of economic dependency.

The Autorité’s opinion provides operators with a number of keys for carrying out self-assessment of their planned or current agreements, with emphasis on the legal and economic factors that are relevant to identify any possible restrictive effects arising from such agreements. Alongside this self-assessment exercise, the Autorité stresses that, in the light of the findings made throughout this opinion, this is an opportunity to make partial adjustments to the framework for the implementation of these rules with a view to enhancing their effectiveness.

1 / The Autorité urges operators to pay particular attention to the way in which they choose the suppliers involved in agreements

Some of the agreements in question are based on a supplier selection process carried out in accordance with criteria that have not always been very precisely defined. It would seem desirable for the operators concerned to take certain precautions with regard to the selection of suppliers, using objective and non-discriminatory selection criteria, given the impact that their choice could have on the supply market.

2/ The Autorité emphasises the general importance of enhancing competition in the food retail sector

Some competition risks could be mitigated by significantly reducing barriers to entry existing on the distribution market.

Specifically, such a reduction could be made via a relaxation of store set-up conditions and a growth in inter-brand mobility. On the latter point, the Autorité is in favour of the provision adopted in the bill on growth, activity and equality of economic opportunity, presented by the Minister of Economy, Industry and Digital Affairs, aimed at limiting the duration of affiliation contracts between stores and their network head.

3/ The Autorité advocates the establishment of a legal obligation for prior notification of any new partnership agreement

In a progress report delivered in January to the Minister of Economy, Industry and Digital Affairs, the Autorité proposed the introduction of a legal obligation on the part of retailers, to issue notification of any new partnership agreements affecting a significant part of the market, before they come into force, so the Autorité can carry out its monitoring role effectively. This proposal has been adopted in the aforementioned bill.

4/ The Autorité proposes an amendment to the procedure aimed at establishing the existence of abuses of economic dependency in order to make it more effective. At the same time, it underlines that the practices in question can largely be examined in the light of the regulations on restrictive commercial practices that fall within the competence of the Ministry and commercial jurisdictions.

The Autorité has drawn up proposals aimed at improving the effectiveness of the procedure establishing the existence of abuses of economic dependency within the context of retailer /supplier relationships. More specifically, it proposes a redefinition of the situation of economic dependency which involves a new wording of Article L. 420-2 of the Commercial Code.

The Autorité nevertheless emphasises that practices liable to be classified as abuses of economic dependency are also liable to fall with the scope of application of Article L. 442-6 of the Commercial Code, which can lead to parallel legal proceedings under the two existing schemes. Therefore, it is only by way of a complement to this procedure (based on Art. L. 442-6), when the damage to the market is likely to be verified, that the proposed new wording of abuse of a situation of economic dependency should be of application.

> Press contact: Rebecca Hébert – tel: + 33 1 55 04 01 81 – Email