The Autorité de la concurrence hands out fines totalling €1,1 billion to Apple for engaging in anticompetitive agreements within its distribution network and abuse of a situation of economic dependency with regard to its “premium” independent distributors.

The two wholesalers, Tech Data and Ingram Micro, were also fined, respectively, €76,1 million and €62,9 million for one of the anticompetitive agreement practices.

Background

After receiving a complaint in 2012 from eBizcuss, a distributor of specialised high-end Apple products (Apple Premium Reseller, APR), the Autorité de la concurrence fined Apple €1,1 billion, as well as wholesalers Tech Data and Ingram Micro €76,1 million and €62,9 million respectively. This decision to impose fines follows dawn raids carried out at the headquarters of Apple and its wholesalers, the litigation for which ended in December 2017.

In total, the fines amount to €1,24 billion and can be broken down as follows:

Apple : 1 101 969 952 €

Tech Data : 76 107 989 €

Ingram Micro : 62 972 668 €

TOTAL : 1 241 050 609 €

Isabelle de Silva, President of the Autorité de la concurrence, stated: “ In the course of this case, the Autorité untangled the very particular practices that had been implemented by Apple for the distribution of its products in France (excluding Iphones), such as iPad. First, Apple and its two wholesalers agreed not to compete and prevent distributors from competing with each other, thereby sterilizing the wholesale market for Apple products. Secondly, so-called Premium distributors could not safely carry out promotions or lower prices, which led to an alignment of retail prices between Apple's integrated distributors and independent Premium distributors. Finally, Apple has abused the economic dependence of these Premium distributors on it, by subjecting them to unfair and unfavorable commercial conditions compared to its network of integrated distributors. Given the strong impact of these practices on competition in the distribution of Apple products via Apple premium resellers, the Autorité has imposed the highest penalty ever pronounced in a case (€1.24 billion). It is also the heaviest sanction imposed on an economic player, in this case Apple (€1.1 billion), whose extraordinary dimension has been duly taken into account. Finally, the Autorité considered that in this case Apple had committed an abuse of economic dependence on its premium retailers, a practice which the Autorité considers to be particularly serious. "

In France, Apple is accused of having implemented three anticompetitive practices within its distribution network of electronic products (except iPhone):

-

Division of products and customers between its two wholesalers Tech Data and Ingram Micro

The two wholesalers concerned were also fined €139 million for having accepted and implemented the product and customer allocation mechanisms developed and supervised by Apple, instead of freely determining their business policy (see details of the fines in the summary table below).

-

These practices have somewhat “sterilised” the wholesale market for Apple products, freezing market shares and preventing competition between the different distribution channels for the Apple brand.

-

Selling prices were imposed on APRs so that they apply the same prices as those charged by Apple itself in its Apple Stores and on its website.

-

The practice resulted in aligning the selling prices of Apple products for end consumers in almost half of the retail market for Apple products.

-

An abuse of a situation of economic dependency on APRs (mostly SMEs), which has manifested itself in particular through supply difficulties, discriminatory treatment and unstable remuneration conditions for their business (discounts and outstanding balances). These practices consisted, in a context where the distributors’ margins were extremely low, in keeping the distributors extremely dependent on receiving products, particularly those most in demand (new products). For example, the Autorité found that when new products were launched, APRs were deprived of stocks so that they could not meet the orders placed with them, while the network of Apple Stores and “Retailers” was regularly supplied. This resulted in a loss of customers, including regular customers. In some cases, in order to meet an order, they were even forced to source from other distribution channels, for example, by ordering directly from an Apple Store as an end customer would have done, in order to supply their customers.

-

These practices led to the weakening, and in some cases, the exclusion of some of them, such as eBizcuss.

While a manufacturer is free to organise its distribution system as it sees fit, to designate different sales channels, to choose wholesalers to supply certain retailers and to reserve direct supply for other retailers, it must comply with competition law as long as the stakeholders in the distribution network are independent and not part of the company. In particular, it is prohibited for a manufacturer who heads a network to undermine competition between its wholesalers by pre-allocating customers to them, to have an agreement with its distributors on the retail prices charged to end consumers, or to abuse the situation of economic dependency of its trading partners, in particular by placing them at a disadvantage compared with its own internal distribution network.

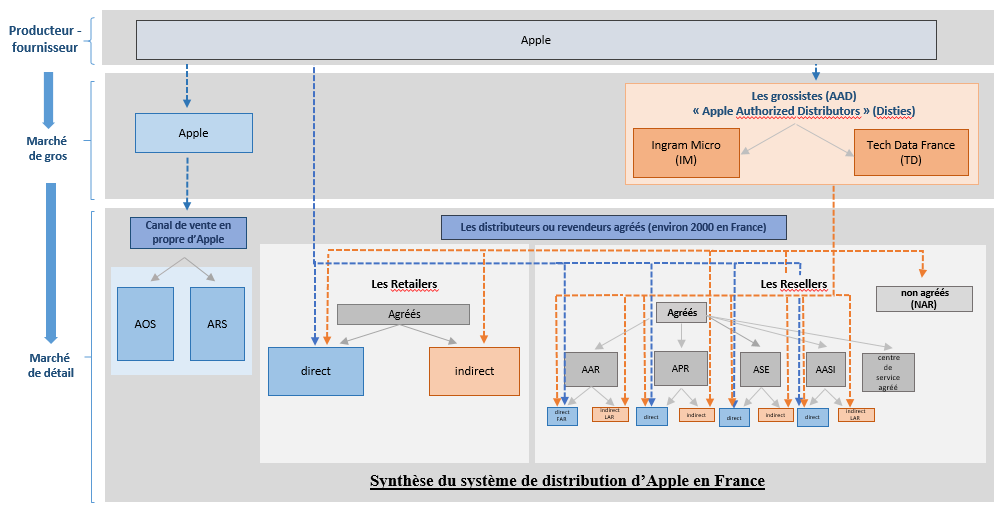

Organisation of the distribution network for Apple products in France

Upstream market

Upstream, Apple sells its products to two authorised wholesalers which are world leaders in the electronics sector: Ingram Micro and Tech Data.

Downstream market

Downstream, the distribution of Apple products is carried out through a network of approximately 2,000 distributors, who can be divided into two main categories, depending on their size and activity.

-

Large generalist or specialised distributors (“Retailers” in Apple terminology)

Apple usually supplies major retailers directly. They may be generalist stakeholders (Auchan, Casino, Carrefour, E. Leclerc, etc.) or specialists, such as Fnac, Darty and Boulanger. In 2017 in France, Apple had 1,800 distributors that it identified as “Retailers”.

-

Specialised dealers (“Resellers” in Apple’s terminology)

Resellers are smaller computer dealers, usually with a limited number of outlets. These SMEs, usually located in city centres, distribute electronic equipment such as computers, tablets, monitors, printers, scanners, hard drives, accessories and software. They also provide services associated with the sale of these products, such as integration, maintenance, repair, etc.

Most “Resellers” are authorised by Apple. They include:

-

Apple Authorised Resellers (AARs), who have a “standard” distribution agreement with Apple.

-

Apple Premium Resellers (APRs), who can join the Premium Network if they specialise in the distribution of Apple products and agree to join an optional program designed to promote a sales environment and provide a high-quality customer experience for consumers. Examples include eBizcuss (Paris, Lyon.)1, ActiMac (Le Havre, Rouen), YouCast2 (Chambéry, Montélimar, Grenoble), IConcept (Pau, Bordeaux, Toulouse, Bayonne), iSwitch (Amiens), Symbiose Informatique (Angers, Lorient, St-Brieuc), Corsidev (Bastia), Alis Informatique (Paris), Easy Computer (Épinal, Vandoeuvre, Nancy and Metz), etc.

Apple’s own network (Apple Stores and the Apple website)

In late 2009, Apple decided to set up its own physical Apple Retail Stores (ARS) in the most important catchment areas. Apple also sells its products directly online to end consumers through its website (Apple Online Store, AOS).

Three penalised practices

-

Restriction of wholesalers’ clientele

The Autorité found that from 2005 to March 2013, Apple had allocated products and customers between its two wholesalers, Tech Data and Ingram Micro. While the two wholesalers were independent businesses,

Apple carefully allocated the distribution of its products, specifying to the two wholesalers the exact quantities of the different products to be delivered to each distributor. APRs were thus hampered in their business, being totally dependent on the stocks decided by Apple both at the wholesale and reseller levels.

Whereas a supplier is free to organise its distribution network by distinguishing between different channels and using wholesalers to market to certain retailers while itself directly supplying other retailers, this is subject to the condition that this division of tasks does not lead to anticompetitive practices. As independent economic operators on the market, wholesalers should have been able to freely determine their business policy, and in particular to freely determine the products they wished to distribute and then the way they would deliver to their retail customers, without interference from Apple.

In the present case, Apple restricted the commercial freedom of its wholesalers by limiting them to the implementation of Apple’s product allocations. The latter have acquiesced to this policy by implementing the allocations decided by Apple. The resulting restriction of competition is all the more problematic as these resellers are in direct competition with Apple itself for the supply of a number of “direct” APRs (resellers with a high turnover in Apple products and therefore have the option of choosing to source their products directly from Apple or from wholesalers).

The system therefore led to a distortion of competition on the wholesale market by completely controlling sales made by wholesalers and by letting Apple favour its own distribution channel by controlling how both direct resellers and “indirect” resellers (i.e., those who obtain their supplies exclusively from wholesalers) were supplied with products.

As a result, the competition that should in principle have existed in France for the sale of Apple-branded products between the different distribution channels, known as “intra-brand” competition, could not fully take place on the wholesale market. The anticompetitive agreement also led to the elimination of competition between the two wholesalers themselves, as well as between the wholesalers and Apple. It also limited competition between final retailers by preventing them from taking advantage of competition among wholesalers upstream.

-

Practice of fixed prices

The Autorité also fined Apple for strongly encouraging APRs to charge the same prices as those charged in Apple Stores. In addition to communicating prices, controlling promotions and monitoring prices charged, the evidence in the case shows that Apple developed a web of contractual clauses and implemented a set of behaviours that left APRs no room for manoeuvre.

Firstly, Apple publicised the prices of its Apple Retail Stores (presented as “suggested” prices) in a variety of media, including its website, accessible to end consumers.

Secondly, several very binding contractual clauses relating to the use of the trademark in communication and marketing materials strictly regulated the conditions under which APRs could organise a promotion. The stipulations, which obliged the APRs in particular to use media and materials imposed by Apple when they sought to offer promotions, were such as to restrict any initiative in this regard, especially since failure to comply with them constituted grounds for immediate termination of the APR contract without notice. In practice, the APRs had only a few promotions, and always under Apple’s control.

Thirdly, a price monitoring system also created a risk of retaliation--in the form of non-delivery--for promotions not authorised by Apple.

For example, one APR, Youcast, stated, “If we applied discounts too systematically and the salesman in our sector knew about it, our competitors could be privileged in their deliveries.”

Or eBizcuss: “We noticed that Apple implements a consumer price policy. In the event that prices are lower than Apple's suggested prices, a local Apple sales representatives contacts us to ask us to raise prices.”

Finally, the investigation showed that Apple--which had a thorough knowledge of the situation of APRs and controlled their supply and the granting of discounts to which they were entitled--was in a position to control their profitability. The lack of economic space and situation of uncertainty also greatly contributed in dissuading APRs from deviating from Apple's “recommended” prices.

Corsidev’s testimony can be cited in this regard: “There’s really no room for manoeuvre. They wouldn't stop us from lowering prices, but the margins are so low that it would be suicidal to do so.”

Likewise, according to Informatique et Prévention, “For Apple products, our price guideline is the catalogue of Apple products with the associated price list: it is up to us to apply a discount depending on the competitive context. It is nevertheless complicated and dangerous to discount our sales given our low margin.”

The retail distribution of Apple products in France currently uses two distinct channels: the “integrated” stores owned by Apple itself (Apple Stores and website) and some 2,000 independent resellers (which are supplied by wholesalers or Apple directly). These resellers are independent economic stakeholders and must therefore be free to determine their business policy (choice of products and quantities ordered, choice of supplier, prices charged, promotions, etc.).

Under severe pressure, the APRs acknowledged that they use Apple's “recommended” prices, which is also corroborated by the price records for the case. As a result, this practice has led to a perfect alignment of selling prices to final consumers for almost half of the retail market for Apple products (with the exception of the iPhone).

By restricting the pricing freedom of APRs, Apple has been able to limit not only competition between the APRs themselves but also competition between the APRs and its own (physical) distribution channels, when they were present in the same geographic area, or online (Apple Online Store). Finally, this practice has harmed consumers who have been deprived of effective price competition in all distribution channels for Apple products.

3. Abuse of a situation of economic dependency

The evidence of the case shows that the APRs were in a situation of economic dependency on Apple and that Apple abused this dependency. The situation, rarely observed in the decision-making practice of the Conseil de la concurrence and Autorité de la concurrence1, results from a complex web of multiple contractual clauses and practices.

Situation of economic dependency of APRs with regard to Apple

The Autorité noted that APR contracts required them to sell Apple products almost exclusively and prohibited them, during their term and up to six months after their expiry, from opening any shop specialising in the exclusive sale of a competing brand throughout Europe. Moreover, the lack of an alternative to the distribution of Apple products was highlighted by the statements of the APRs: all of them stressed that their customers were strongly attached to the Apple brand and that leaving the Apple world would result for them in the total loss of value of their business, in irrecoverable investments and in significant costs for refurbishing stores and training staff, which would be impossible to achieve in the short term for operators in already fragile situations.

Abuse

Article L. 420-2, paragraph 2, of the French Code of Commercial Law (Code de commerce) prohibits, whenever it is susceptible to affect the functioning or structure of the competition, the abusive exploitation, by a company or group of companies, of the condition of economic dependency in which a customer company or supplier finds itself vis à vis such company.

In the present case, the Autorité has identified a set of rules and conduct implemented by Apple which, taken together, constitute an abuse by restricting the commercial freedom of APRs in an abnormal and excessive manner. These various factors have had a direct impact on the business activity of the APRs beyond what an economic stakeholder can reasonably expect from a commercial partner and have created an imbalance in their relationship with Apple.

The observed behaviour consisted in particular of supply difficulties, discriminatory treatment, unstable remuneration conditions for APR activity (discounts and outstanding balances), and discretionary implementation of certain rules.

-

Delays or lack of supply, resulting from the allocation system put in place by Apple and the disadvantage suffered by APRs compared to Apple Stores and Apple’s website, which for their part are always promptly supplied with Apple products.

Most APRs reported that they regularly encounter delivery problems, particularly during new product launches or at the end of the year. They faced restrictions in supply due to the customer allocation policy implemented by Apple, either directly or through its wholesalers. Some products proved to be totally unavailable to APRs.

In addition, when new products were launched, the APRs often found themselves without stocks so that they were unable to meet the orders placed with them while the network of Apple Stores and the “Retailers” were regularly supplied.

The Autorité has demonstrated that these delays or refusals of supply were not the result of stock shortages, since the supplies were available in the “Apple Stores”, the “Apple Online Store” and at “Retailers”.

This discriminatory treatment of APRs was all the more serious in view of their particular situation with regard to the manufacturer. On the one hand, APRs are commercially independent operators, unlike the “Apple Stores”, and must purchase the goods in order to carry out their distribution activity. On the other hand, they are forced to stock Apple products (which must account for 70% of their sales in order to maintain APR status) and are placed in a situation of economic dependency, unlike the “Retailers”, who carry on a general distribution business and are not in a position of dependency on Apple.

-

Given Apple’s discount and outstanding balance policy, there is uncertainty about business terms and conditions

The APRs were kept in uncertainty about the volume of their supplies, as well as about the terms of the discounts offered by Apple. The system of rebates granted to APRs was discretionary in nature, which created uncertainty about the amount of rebates paid to APRs, in addition to uncertainty about their deliveries. Given the significant and growing importance of rebates in the profitability of APRs and in their ability to generate a positive margin, the unpredictability of the rebate system, a result of the contractual clauses and their conditions of implementation, constitutes an abuse of a situation of economic dependency.

Among the accounts from APRs, we can cite that of Acti Mac as an illustration: “Regularly receiving only a minimal supply, we cannot commit ourselves to delivering to our customers who, weary of the effort, cease soliciting us by ordering either from the Store or by going to the nearest ARS.”

An APR also noted: “We never know when a new product is going to be launched, usually there are rumours (...) Apart from the iPad and iPhone, product launches are not announced. For other products there is no announcement, we are usually informed by the press, or we can deduce that there will be a product announcement when some Apple Stores announce a new product launch (...). For the iPad we are not allowed to communicate about the launch.”

The particular situation of eBizcuss demonstrates the concrete and effective impact of Apple’s abuse of a situation of economic dependency. As eBizcuss stores located in Paris and Lyon were unable to receive the Apple products necessary to satisfy the demand of its own customers or to compete with Apple Stores in terms of price or level of service, eBizcuss stores located in Paris and Lyon were placed at a commercial disadvantage compared to Apple Stores, resulting in a decrease in turnover of these stores on the order of 15%.

The president of the APR association also complained of a real “strategy of exclusion on the part of Apple” with regard to APRs, as did Alis Informatique, which evoked “a premeditated death”. You Cast blames its financial difficulties and liquidation proceedings on its “cash flow lag problems related to delivery problems with Apple products”.

When a manufacturer keeps its distributors dependent on it, it must take care not to abuse this dependence, i.e., not to restrict their commercial freedom beyond the tolerable limits and not to put them at a disadvantage in relation to its own internal distribution network.

With the APRs, Apple benefited from a network whose obligations imposed on distributors were similar to those of franchisees, without itself being subject to the obligations of a franchisor, thus depriving them of the consideration attached to this form of distribution. Thanks to the network, the company no longer needed to set up its own stores throughout France, which has enabled it to focus on locating Apple Stores in the most profitable areas. Subjected to the conditions of hardship comparable to those of an integrated operator, while having to assume the commercial and financial risks of an independent company, the APRs enabled Apple to distribute its products throughout France without having to invest in its own stores and without its direct sales (online and physical stores) being affected by competition.

These practices have led to the weakening and, in a number of cases, the exclusion of certain APRs, such as eBizcuss.

1 eBizcuss operated as an APR in France from 2008 to 2012 and then withdrew from the French market. It remains active in Belgium (Macline).

2 You Cast a été repris en partie par Ephésus.

3 Decisions 01-D-49 of 31 October 2001 relating to a complaint and request for interim measures by Concurrence concerning Sony and 10-D-08 of 3 March 2010 relating to practices implemented by Carrefour in the local general retail food sector, concerning a franchise network.

> See full text of the decision 20-D-04